The Boston Globe

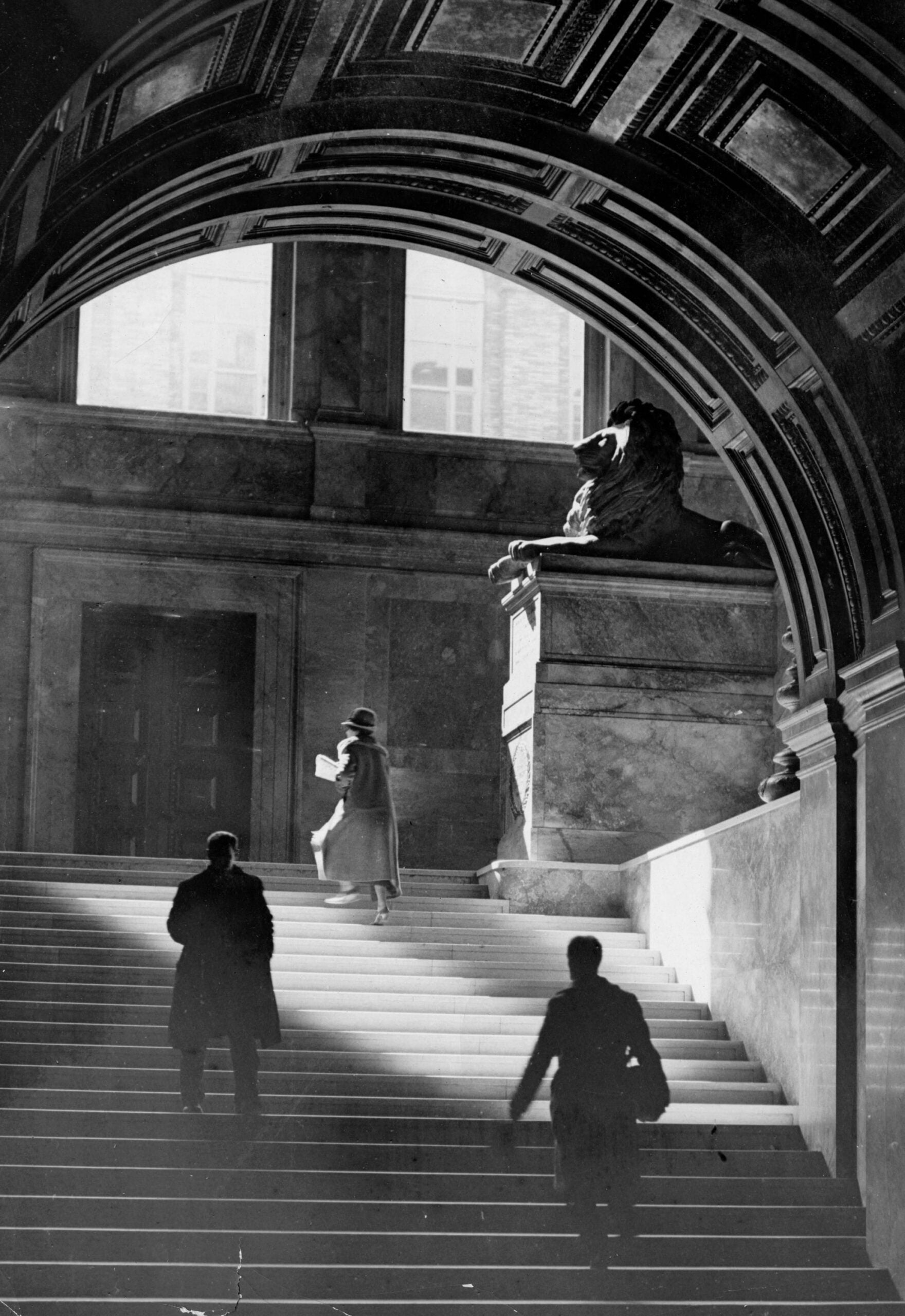

The resplendence of the Boston Public Library’s McKim Building unfolds with each step up the grand staircase.

Past the imposing stone lions, the golden-hued stairwell gives way to an airy gallery of murals, a millennium-spanning celebration of the muses. Nearby, a narrower stairway leads to the hushed third floor, where people wander the opulent gallery to untangle John Singer Sargent’s “Triumph of Religion,” a monumental cycle of murals the artist left unfinished despite nearly three decades of work.

Inevitably, some will try the leather-clad door at the end of the gallery, which seems to promise yet more wonders beyond.

But the door is locked.

It has been closed to the public for more than a decade, concealing a once-grand enfilade of vaulted ceilings, interior arcades, and elevated walkways that wrap around the library’s courtyard.

The rooms, which rival many of the building’s most celebrated spaces, now warehouse a Narnia-worthy collection of the library’s holdings — everything from sculptures of Joan of Arc and a portrait of Samuel Johnson, to a room of illuminated dioramas, where a pair of miniature boxers stand frozen in mid-fight, as though before a roaring crowd.

There are neoclassical sculptures that peek from beneath plastic, a weathervane in the shape of a cod, a printing press that belonged to artist Hyman Bloom, and a set of golf clubs once swung by author Cleveland Amory. And that’s to say nothing of the myriad architectural plans, microfiche, administrative records, card catalogues, and archives piled about in boxes and in crates.

At 130 years old, the McKim Building is nearly as iconic as the collection it houses. Designed by architect Charles Follen McKim, it is a sort of secular cathedral, exalting the life of the mind.

But today, nearly 40 percent of the building — essentially the entire third floor — lies dilapidated and inaccessible to the public. Paint peels from its walls and ceilings. Crumbling plaster has exposed masonry. Leaky pipes have prompted library officials to turn off the heat, meaning most of the palatial third-floor rooms have no climate control at all, a wrecking ball of temperature swings and humidity.

Now at a crisis point, the unusable spaces and their at-risk contents have prompted library officials to begin imagining a massive — and massively expensive — overhaul, one that would not only restore the third floor but also reshape one of the country’s oldest and most vaunted library buildings.

BPL president David Leonard said any renovation must not merely safeguard the building, but also secure the library’s collections, making them (and the physical building) more accessible to the public.

“We have an obligation to our collections and to the building itself, which we like to think of as part of the collection,” Leonard said while touring the McKim.

The library recently received a $5.5 million gift from an anonymous donor to study the building and its systems. It’s a preliminary step to understand what obstacles and opportunities the building may present as a renovation project that seeks to update the 19th century structure to meet the demands of 21st century library patrons.

Once the five-year planning phase is completed, leaders hope to enter the project’s design phase.

Beth Prindle, BPL’s director of research and special collections, called the renovation effort “a once in a multiple-generation opportunity.”

“The McKim transformation and rebirth is a clarion call,” she said. “We collected this incredible, irreplaceable collection, and we need [the public] to help us steward it, not only for [today], but for future generations.”

In addition to branch renovations, BPL has completed two major capital projects on its central library over the past decade. In 2016, the library unveiled a $78 million renovation to its lending library in the 1970s-era Boylston Street Building. That was followed in 2022 by a $16 million project that carved out a state-of-the-art facility to house its vast special collections of rare books and other historic items.

The cost of renovating the McKim, however, would likely dwarf those earlier projects. A 2021 master plan estimated construction costs at $325 million, but the final project could cost significantly more.

Leonard, who compared the project’s potential cost to building a new public high school, said the library will have a better price estimate in a year or so, but “regardless, it’s a large, triple, hundreds of millions of dollars.”

“There’s a world of questions that need to get answered,” he said. “But at some point we’ll have a number, and we’ll need to ask: What is the city really up for? There’s no way to be successful at raising that amount of money without the city, the state, and private philanthropy all being engaged together.”

The city has so far pledged $50 million toward the renovation, which Mayor Michelle Wu said has been sorely needed for years.

“But it feels more urgent than ever,” she said, particularly in a political climate “that is often trying to restrict or proscribe who has access to which books.”

Wu added that the federal government’s “unpredictability, or even outright hostility” has complicated the funding equation.

Still, “we have to find a way to see this through,” she said. “That will require a combination of city dollars, partnerships, philanthropic support, and hopefully other sources of funding.”

But perhaps the larger challenge will be in the realm of design, renovating a municipal building, and National Historic Landmark, whose symbolism is deeply entwined with the city’s identity.

Not only was Boston the first large US city to boast a public library, but it later pioneered the branch system, bringing books to neighborhoods across the city. A 1972 addition roughly doubled the central library’s footprint, creating a 1 million square foot complex that spans an entire city block.

Meanwhile, the collection itself has swollen to become one of the country’s largest, a sprawling horde of more than 20 million objects that contains everything from medieval manuscripts and a rare edition of Shakespeare’s First Folio to current bestsellers and even a consecrated loaf of bread.

The library has hired a cultural consultancy group, PAM, to help officials think through a host of issues during the planning phase, everything from public space and collections care to back-of-house operations and overall accessibility.

PAM strategy director Abigail Smith Hanby likened the McKim’s architecture and collections to a cathedral in their power to transform visitors.

These libraries “were designed so majestically to make you feel awe, to be inspired, to see something grand and be a part of that thing that is grand,” she said. That is “the creation of knowledge, and [the McKim] is one of those first places for that creation of knowledge.”

One clear priority is to leverage the library’s special and research collections. While walking the third floor, Leonard envisioned converting a series of arched nooks into private meeting rooms enclosed by glass, while Prindle imagined a cafe in a particularly grand room off the Sargent Gallery.

Leaders also want to improve accessibility in the stair-dependent McKim, adding elevators, creating better connections with the Boylston building, and animating the McKim’s many rooms that are today open to the public, but woefully underutilized.

Among the more ambitious — and perhaps controversial — ideas is constructing an elevated walkway across the library’s central courtyard to connect the two buildings, or perhaps even enclosing the courtyard in a way that retains its outdoor feel.

“Is there a way to do a transparent roof,” asked Leonard, who added that an enclosure would enable year-round use of the outdoor space. “Let’s have those conversations.”

Another big priority: How to better store and care for the library’s research collection, which numbers some 16 million objects. The Boylston building, which houses roughly 4.5 acres of storage across four floors, is at capacity. The library’s auxiliary storage facility in West Roxbury is similarly full.

– Jessica Rinaldi/Globe Staff

That means many of the remaining objects — the furniture, the archives, those Joan of Arc sculptures — have wound up on the third floor, a conservator’s nightmare.

Prindle said the library has a team and “triage” protocols in place in the event mold is found, as happened in 2015, when the library temporarily closed its rare books department following a widespread outbreak.

“My team would sleep so well at night if we were not worrying about things happening to the building that affect the collections,” said Prindle. “I honestly think that is the biggest danger we are dealing with right now.”

Hanby’s firm, PAM, has also brought on William Rawn Associates, the architectural group that led the award-winning renovation of the Boylston Street Building.

Rawn principal Cliff Gayley said that when the firm began working on the project, it considered the Boylston building the “complementary opposite” of the McKim.

“The worldview that had designed this space no longer existed,” he said while touring the redesigned library. “Something more radical needed to happen.”

The same could be said today of the McKim Building, which was partially renovated in the 1990s. The question now, Leonard said, is what sort of library does Boston want?

“In some ways, we’re kind of trying to finish work that was never done,” he said. “We hope this is a journey that we’re all going on together.”