Local News

When students put on their coats and hats to go outside for recess Thursday, after several days of indoor play, some of the 6-year-olds asked an anxious question, the teacher recalled: “What about the ICE people?”

PORTLAND, Maine — Shandy Priddy, a delivery driver for Target in Portland, Maine, was dropping off a package at an apartment complex Friday morning when a stranger approached with a startling question: Would Priddy drive her son to school?

On the fourth day of an unprecedented federal immigration crackdown in the state, Priddy, 48, a mother of three, said she understood instantly.

“She looked petrified, like she did not want to step out of that corridor,” said Priddy, adding how the woman had explained that she was an immigrant from Congo and that her husband had been taken by immigration agents the previous day.

“I know that pressure,” Priddy said, “of having security and then not having it.”

As the federal surge began last week, officials with the Department of Homeland Security said it was targeting 1,400 “criminal illegal aliens who have terrorized communities” in Maine. On Monday, the department said immigration agents had arrested more than 200 people so far. Several Democratic elected officials and lawyers for detained immigrants have said that at least some have no criminal records.

In Portland, a city of about 70,000 people that is home to many of the state’s estimated 50,000 immigrants, federal officers have been stopping cars, detaining motorists and staking out apartment buildings.

As of Monday, more than 60 people arrested in the Maine operation had sought emergency legal help from the Immigrant Legal Advocacy Project of Portland, its leaders said. At least eight detained Maine residents had been sent to detention centers in Louisiana.

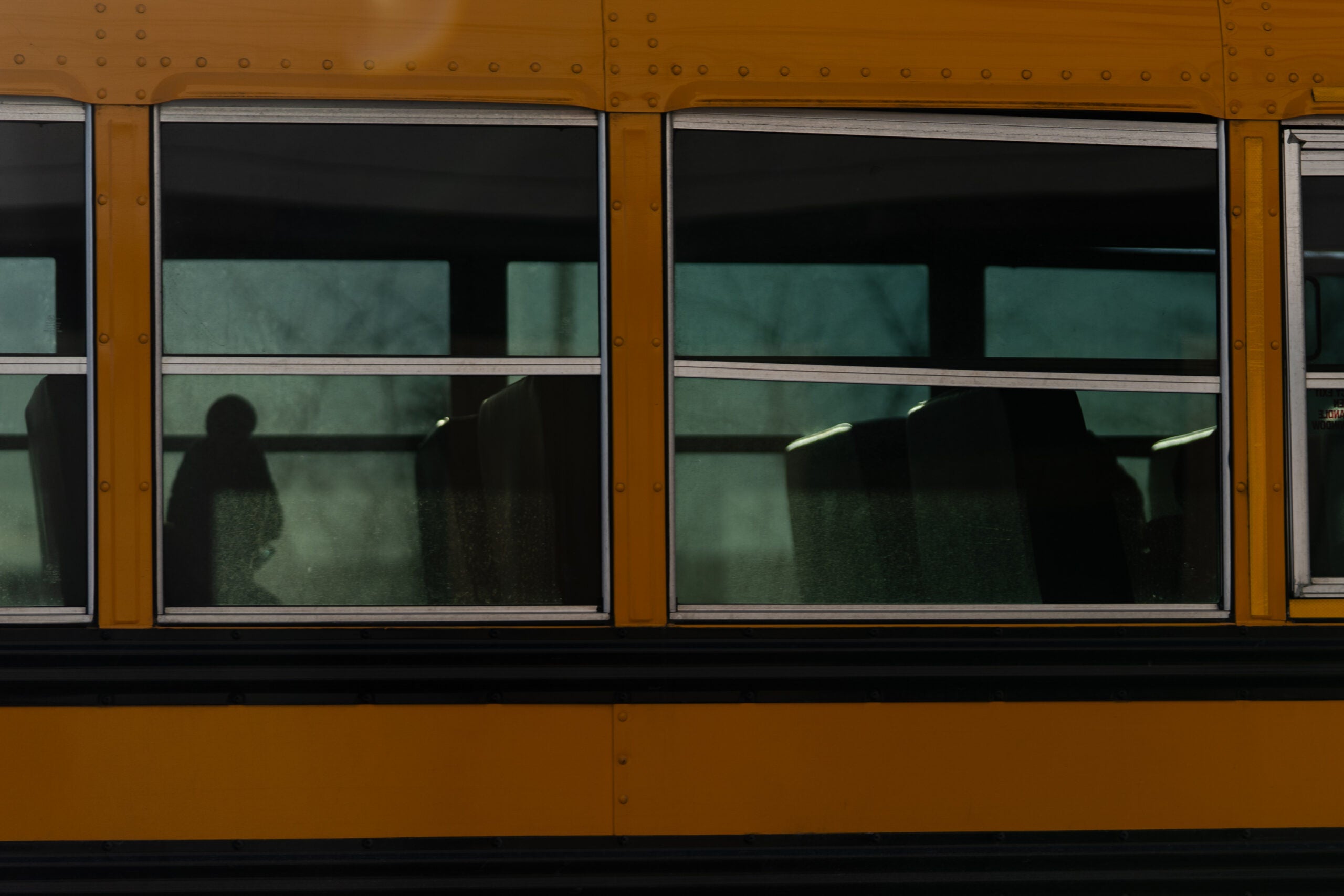

As unmarked SUVs circulated in the small city and social media filled with reports of arrests, some of the most consequential impacts were quietly felt at public schools, where teachers and administrators tracked escalating student absences and tried to offer families assurances of safety.

Though Maine is one of the whitest states in the nation, Portland’s school system is a testament to the significant number of immigrants, many from African countries, who have settled in the state in the past two decades. More than half of the system’s 6,200 students are Black, Hispanic, Native American, Asian or multiracial. Nearly 30% are English language learners; students speak more than 60 languages.

At some schools, 25% to 30% of students were absent last week, many of them immigrants or children of immigrants. Some did not show up because their parents had been detained. Others were kept at home by fearful family members who stayed inside to reduce their risk of encountering agents from Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Absences were higher among some groups, said Sarah Lentz, chair of the Portland Board of Public Education: 41% of multilingual students, 39% of Hispanic and Latino students, and 34% of Black students were absent districtwide Thursday, compared with 6% of white students.

In missing school, children are also losing access to other essentials, school leaders said, including free breakfasts, lunches and snacks; bags of food sent home to their families on weekends; counseling and legal services; and the use of showers and laundry facilities that were unavailable to some at home.

“We have almost 500 students who are housing insecure,” Lentz said. “If kids are not in school, their basic needs are challenged.”

In one elementary school classroom in Portland, roughly half of students were missing each day last week, said their teacher, who declined to be identified because she was not authorized by the school district to speak to the news media.

When students put on their coats and hats to go outside for recess Thursday, after several days of indoor play, some of the 6-year-olds asked an anxious question, the teacher recalled: “What about the ICE people?”

At another school, where kindergartners blow a kiss every morning for each absent classmate, children sent kiss after kiss into the air last week.

On Monday, city schools were closed after a storm left 12 inches of snow on the ground. School officials are planning to discuss options for limited remote learning at a meeting Tuesday, but said in a letter to parents that “we will not shift to remote learning across schools unless necessary for safety reasons.”

Across the city last week, nonimmigrant parents and community members organized “watch” teams to help at-risk families feel safer, with volunteers in bright yellow and orange vests patrolling playgrounds and school entrances daily, carrying whistles and keeping eyes on student pickups and drop-offs.

“We’re here in Portland because of the diversity — it’s a huge asset — and now our kids’ friends no longer feel safe coming to school,” said Katie Mears, 44, a parent who helped organize watches at one elementary school. “If we can use our privilege in a useful way, and stand out in the cold for an hour or two to make people feel safer, it’s 1,000% worth it.”

Their efforts took on new urgency after an ICE action unfolded a block or two from the school Thursday, stoking fears. In another incident reported last week, a mother was detained while driving home from dropping off her child at Portland High School. One of the woman’s daughters told The Portland Press Herald that her mother is an immigrant from Congo with a pending asylum application, four children and no criminal record.

She is also an employee of the school district, the superintendent, Ryan Scallon, wrote in an email to families Saturday, calling her “a valued member” of its facilities team. He said the woman is legally approved to work in the U.S. and passed a background check clearing her to work in schools.

“Her detention has hurt our community and left her children with no head of household,” Scallon wrote.

In Lewiston, a smaller city 30 miles to the north that is a focus of the ICE operation, African refugees and migrants started settling in large numbers more than two decades ago, including thousands who fled civil war in Somalia. State education officials said Lewiston was also among the cities reporting widespread student absences last week, along with Westbrook, South Portland and Biddeford.

Multilingual students in the state had been scheduled to take a federally required English proficiency test last week. State officials said that in response to widespread absences, they had sought and were granted an extension for the testing.

Nsiona Nguizani, 42, an immigrant from Angola and an organizer with Portland Empowered, a nonprofit that helps immigrant children adjust to American schools, said he was concerned that students who were already behind would lose more ground if the federal crackdown persisted.

“The gap is so big,” he said, “and we cannot afford to stay home while schools keep going.”

Even if virtual schooling is offered, he said, younger children cannot be left alone, forcing parents to stay home or find other caregivers and adding to families’ financial burdens. He said he was encouraging parents to send their children to school, and to resist fear tactics that might be intended to pressure them to self-deport.

Families must balance the need to “keep people safe and at the same time keep living,” he said.

Classrooms were not the only place where children’s absences spurred concern. Doctors said that they, too, were taking note of canceled appointments — and worrying about missed vaccinations and screenings, and emerging health concerns that might go untreated.

“Kids are already missing appointments, especially newborns,” said Dr. Cheryl Blank, a Portland pediatrician. “If they’re not going to the doctor, there’s a chance you’re missing something that you could potentially catch.”

In South Portland on Friday morning, Priddy said she had happily taken a break from making deliveries to drive a panicked stranger’s second grader to his school. The mother rode along with her, feeling safer because a white U.S. citizen was at the wheel, Priddy said. The woman shared that she was nine months pregnant, that her husband had done nothing wrong and that they had no other family nearby, Priddy said.

When they went their separate ways, she said, she gave the woman her cellphone number and told her to call if she needed anything.

“It takes a community,” Priddy said. “I told her, you don’t know me, but I will do my best.”

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

Extra News Alerts

Get breaking updates as they happen.