Local News

The author/Dylan interviewer/CNN commentator will discuss Dylan and Joan Baez at Boston’s Folk Americana Hall of Fame event Sept. 27.

When I was in seventh grade, I bought Bob Dylan’s “Self Portrait” from a discount bin for my first Sony Discman.

Like many, I grew up on Dylan. So my mind melted, right there on the drive home from the Silver City Galleria, when I heard Dylan duet with himself on “The Boxer” using two voices: that “Nashville Skyline” crooner voice and his real voice.

Every critic and fan likely has their take on that album — awful, genius, joke — but to me, at that moment, it was Dylan using his voice like layers of paint on top of each other. Like a self-portrait. And it cracked something open for me.

I would spend years thinking (and writing) about this mystery wrapped in a riddle. Einstein disguised as Robin Hood. Jokerman, manipulator of crowds, a dream twister.

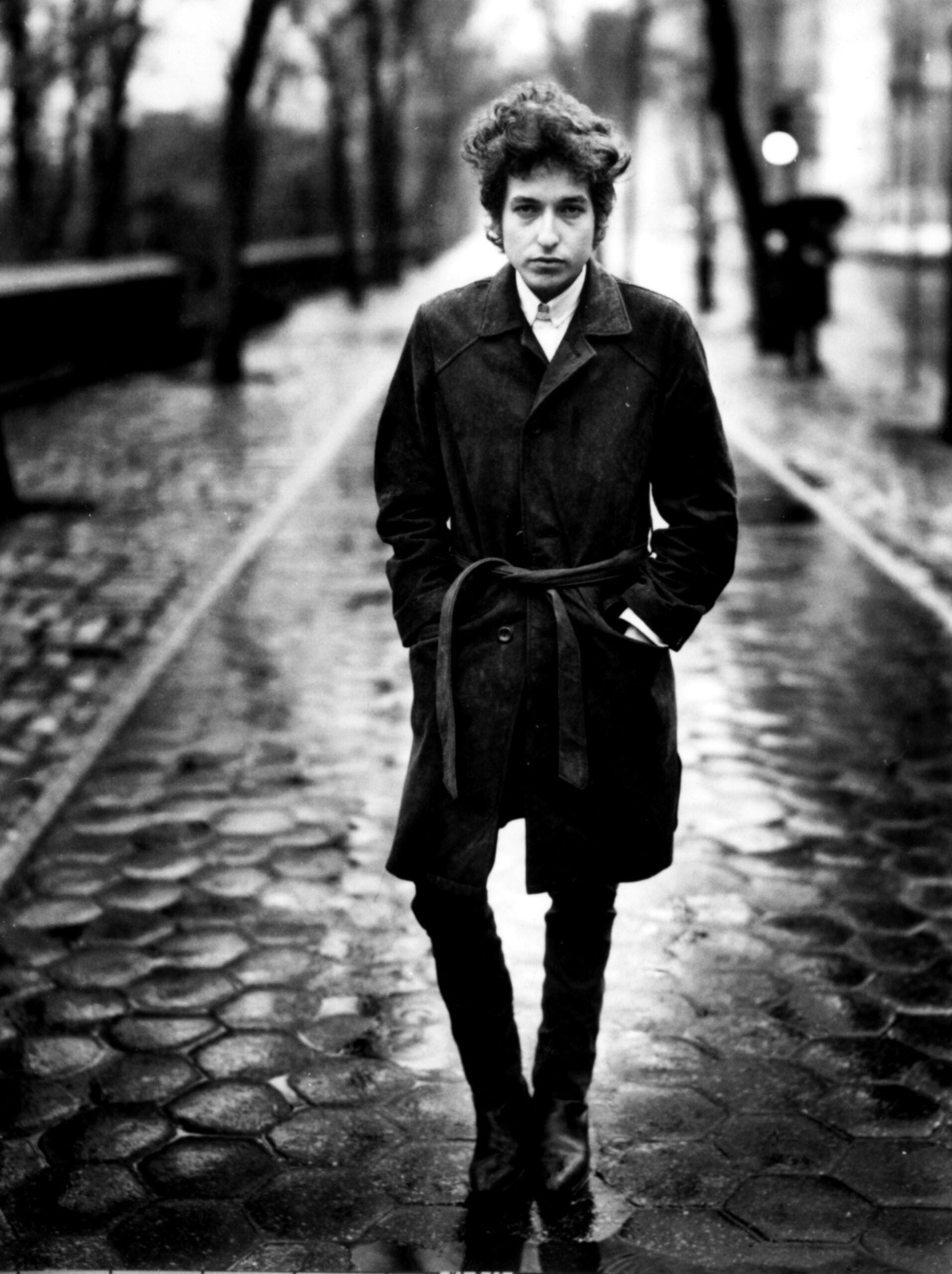

This Minnesota college drop-out/Little Richard fan Robert Zimmerman, who created his own myth — a poet-ghost named “Bob Dylan” — from nothing, from iron country dreams and Woody Guthrie imitations.

Who built his own legend by changing masks — country boy, folkie-with-a-message, Christian rocker, face-painted carny barker, old-time blues dandy, piano lounge crooner — and never letting one slip.

We will never figure out this North Face-wearing octogenarian, who, I should add, tweeted one of his now-classic and totally random birthday shoutouts on Sept 25: “Happy Birthday Shostakovich. Tea for Two — Fantastic! You won the bet.” (Apparently a bet between two Russian composers in 1927. Innocuous, out-of-the-blue — right on brand.)

And yet — legions of us love to play at it. Man’s a walking Sudoku.

When I heard that historian/author /Dylan interviewer Douglas Brinkley was coming to Boston, in part, to talk Dylan in Newport, I had to reach out.

When I told Brinkley I grew up with Dylan, he didn’t miss a beat:

“You and I are going to be best friends. I’ve been interviewing and writing about Bob Dylan for decades and the spirit of my visit to Boston is keeping the Dylan flame alive. I think he’s the most remarkable artistic music figure of modern times. He’s inspired me since childhood. I used to busk around Europe singing Dylan songs, and then using that money to go see Bob on tour.”

He tells me there’s “seldom a day I don’t listen to Dylan” and “I’ve seen him in concert live a ridiculous amount of times; I don’t count.”

(Maybe we are going to be best friends?)

The professor of history at Rice University, a CNN U.S. presidential historian, contributing editor at Vanity Fair, and author, Brinkley sits on the boards of the Bob Dylan Center, the Woody Guthrie Center, and the Bruce Springsteen Archives.

He speaks Saturday about Dylan and Joan Baez at a sold-out symposium, “Wasn’t That A Time: The Boston Folk Revival 1958-1965.”

This first collab between the Bruce Springsteen Archives and Boston’s Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame aims to shine “a light on that history through discussions with artists, academics, and those who were there.” It’s the first in a planned series of events between the organizations.

Other notable symposium speakers include Peter Wolf, Tom Rush, author Elijah Wald, Cambridge folk scene stalwart Betsy Siggins, Noel Paul Stookey of Peter, Paul & Mary and more.

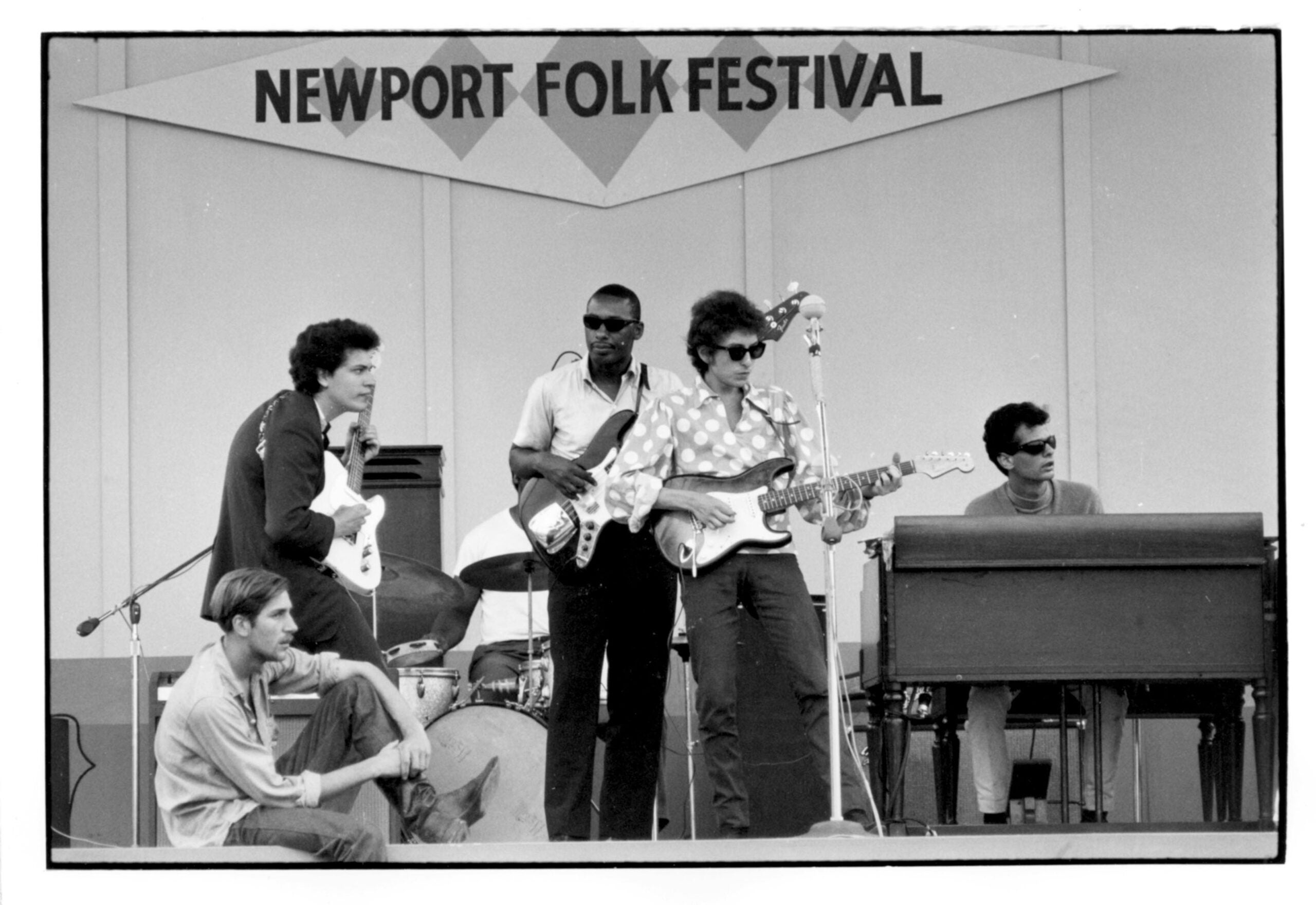

Brinkley, 64, takes part in two panel discussions: “Dylan Goes Electric at Newport ’65” and “Joan Baez in Cambridge and Beyond.” Both look to be fascinating.

As Baez told me previously, “Cambridge, my Boston days … were such an important part of my life. It was the beginning of the folk boom, and I was the right person at the right place at the right time.”

Meanwhile, Cambridge native Elijah Wald wrote “Dylan Goes Electric!” (2015), which inspired “A Complete Unknown.”

Whether or not there was booing at that infamous fest, believing in the boos is key in order to build the myth of Dylan as an outlaw rocker. Dylan must know that: “Dylan was involved with this project before Chalamet or James Mangold,” Wald told me, previously. “The booing was absolutely essential to Dylan’s myth, [as] proof that he was not selling out to become a rock star.”

For an artist who has spent his career like a spelunker — headlamped and hunting for truth in the abstract in this cave of life as it grows ever dimmer — Dylan runs fists pumping from small personal truths and biographical facts.

Dylan doesn’t really do press. Not seriously, at least. (See: any 1965 press conference clip.) Doesn’t need to. Rolling Stone headlines follow him around; you get the distinct sense that the more absurd, the more totally random, all the better for this school kid laughing into his fist.

One rare exception: Brinkley. The Austin resident seems to be someone Dylan trusts to sit and speak with honestly — and more than once.

For all you Dylan fans out there — all you keepers of the flame — if you weren’t lucky enough to snag tickets for today’s sold-out symposium, I called the professor to pick Brinkley’s brain for you. We talked Baez, Newport, Dylan’s place in history — and I learned a bit about Robert Zimmerman: history buff and Cormac McCarthy fan.

You said you’re coming here to “keep the spirit of Dylan alive.” I feel like he’s tapped you as the guy he’s chosen to talk to. You’ve interviewed him multiple times.

Well, as he told me, he doesn’t like newsy people. He has a trade as a songwriter and musician, and I have a trade as a historian. He likes trades-folks, not looking to seize a gotcha, or morning headline.

I love his art so much. When your feelings about somebody are authentic and from a good spot, people read that. Some people tend to like to talk to historians more than journalists because they’re not just looking to make instant news.

How did this connection start?

I wrote a Rolling Stone cover story of Dylan [in 2009], and I spent a lot of time in Paris and Amsterdam with him. That developed into a friendship.

He loves American history, so he likes to talk about the Haymarket Affair in Chicago, or the Battle of Gettysburg. Or it could be the Seminole Tribe in Florida. He’s deeply invested in U.S. history. And very deep in Roman history, French Revolution, World War I. The genesis of any friendship is anchored around mutual interest.

So the overall theme of the symposium is Cambridge’s folk era.

That folk world of Club 47 from 1958 to 1965 has not received the press like Cafe Wha, or the folk center and things in New York. So it’s nice that Cambridge is able to carve out its place in the history of American music. Locals should use this as an opening salvo to learn more about that aspect of your local culture.

I’m hoping this has an educational value, to remind people or educate people that post-World War II music wasn’t just Chicago, St Louis, New York City. Cambridge played a crucial role in allowing the ‘60s counterculture to emerge, and in triggering the folk revival.

You’re also on the Baez panel.

Joan Baez has still not been understood properly as a major figure in U.S. history, in [the context of] Dylan history and folk music, certainly — but also for her non-violent protest and collaborations with people like Martin Luther King Jr and Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez.

She’s associated with California, but it’s important that the East Coast pays tribute to Baez.

What would you want New Englanders to know?

Just what a phenom she was at an early age, and how she was able to stoke the consciousness of the time on issues with civil rights and the banning of nuclear testing and the plight of the agricultural farm workers.

She was seminal. When Baez was going to be at an event, it attracted all sorts of other people. She was a luminary before her time. When you’re in your early 20s, and you’re a household name on the cover of TIME — it’s heady stuff. The way she’s conducted her long career with such dignity and purpose is remarkable.

This is my first time being able to reflect on her in a public forum. I’m looking forward to it. And I love her album, “When Baez Sings Dylan.” Everybody’s covered Bob Dylan, but Baez has some covers that bowl me over.

You’re also on the panel with Elijah Wald, whose book was adapted into the Dylan biopic. Have you seen it?

I did. I enjoyed it. I thought Timothée Chalamet earned his spurs, working hard to capture some of the magic of young Bob Dylan. And introduced Dylan’s back-catalog to a new generation.

That was exactly my hope for it. That Chalamet might be the key that unlocks the Dylan door.

It was a gate of enlightenment in that regard. When you’re really into Dylan, the way you and I are, it wasn’t like there was something you learned intellectually. I mean, that’s a movie an 8-year-old could watch. It served as an introductory door-opening.

Your talk with Wald is “Dylan Goes Electric, Newport ‘65.”

I can’t wait to talk with Wald about that. Dylan told me that it wasn’t scary for him in Newport at all. It was “The Ed Sullivan Show” that was defining, because everybody in Minnesota — including his mom and dad — was watching Ed Sullivan. [Dylan famously walked off the set on May 12, 1963, after CBS told him he couldn’t sing “Talkin’ John Birch Paranoid Blues.”]

All of his friends from [home] — couldn’t believe it: Robert Zimmerman, now Bob Dylan, is on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” the biggest show in the country.

That censorship moment — when CBS refused to let him sing “John Birch”— they wanted him to do Irish folk songs or something — he told me he just froze. It’s nerve-wracking. [To be told to change your set] shortly before you’re going on TV with the whole world watching. He just walked out. It was unsettling.

At that point, he’d become an outlaw [in the public view.] But it wasn’t just an act of hubris. It was disappointment that the big gig got blown. He just said, “I gotta get out of here. It’s wigging me out.”

That’s interesting. What did he say about Newport?

It wasn’t a key transition point. He’d played rock and roll, as you know, in high school. [At Newport] he was trying to sell his new album, play his new songs. It may be inflated as a mythological moment more than warranted. It’s just the folk purists who thought it was an act of quasi-betrayal.

Elvis Presley once said, “I’m just doing what I feel like doing.” Every artist has to do that. The point of being Mark Rothko or Helen Frankenthaler is shattering paradigms.

But what did he think happened in regard to booing? Because depending on who you ask, you get a different answer: no one booed, everyone booed, only folkies booed.

Let’s call it the fog of war. Go to a battle in Vietnam or Iwo Jima, and one veteran will say this happened, another will say this. I think he thinks Wald’s book is pretty good.

But in his life, it wasn’t the moment we think of it as: that moment of Holy God, what am I doing? That self-assessment had come earlier with Ed Sullivan.

It’s interesting that Dylan wanted to option this story, though, because it’s a key part of the myth.

Yes. And from a screenplay point-of-view, that book provided a narrative where — Remember, Dylan loves cinema. So in terms of what would make a good movie, this one is backed by a quality musicologist in Elijah Wald, who wrote about Robert Johnson, somebody that Dylan really listens to now. Bob’s going out as a bluesman. He’s encyclopedic on every aspect of blues.

You’ve mentioned he’s into American history, world history, the blues. What else does he get passionate about?

The plight of Native Americans in history and how it needs to be taught more, understood more. His interest in the Civil War. He’s really learns the music of that era — what was the music like in the South in the 1860s? The north in 1890? I don’t know anybody else who has it to that degree.

He’s a huge reader. Any books you talk about?

Cormac McCarthy.

I can see that.

A lot of really good nonfiction. People are always giving him something to read. He’ll read on the tour bus. He also songwrites on the road, more than in California. At Point Dume, he’s got a lot of children, grandchildren.

It’s easier when you’re moving and playing at night, because when you’re done with the performance, you still have adrenaline. If you drink coffee and have a notebook, you can start working on song-crafting. Traveling on a bus, it’s a chance for him to be everywhere, and yet be self-contained.

That’s a great point. So as a U.S. historian, how do you see Dylan in the pantheon?

There’s nothing like him. I feel privileged to live in the age of Bob Dylan, because it’s rare that you have an artist of such magnitude in your midst.

How many senators do you know from 1840? 1880? Who were the Vice Presidents to these people? You can’t name them. But certain artists will be around forever. Dylan’s art is timeless. It captures the essence of America through American music and Western expansion and blues and jazz and the key districts like Greenwich Village or Cambridge.

And [the Bob Dylan Center] in Tulsa has been great to see all of Dylan’s lyrics — the different versions, how his mind works as an artist, how he crafts the art form he’s supreme at, which is a lyricist. But I also think Dylan’s deeply underrated as a singer, and that his voice is a voice of our time and will live on forever.

To me, he’s Frank Lloyd Wright, Walt Whitman, Toni Morrison — in this rare league as one of the most seminal American artists of all time.

Interview has been edited and condensed. Lauren Daley is a freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected]. She tweets @laurendaley1, and Instagrams at @laurendaley1. Read more stories on Facebook here.

Sign up for the Today newsletter

Get everything you need to know to start your day, delivered right to your inbox every morning.